What is Holy Trouble?

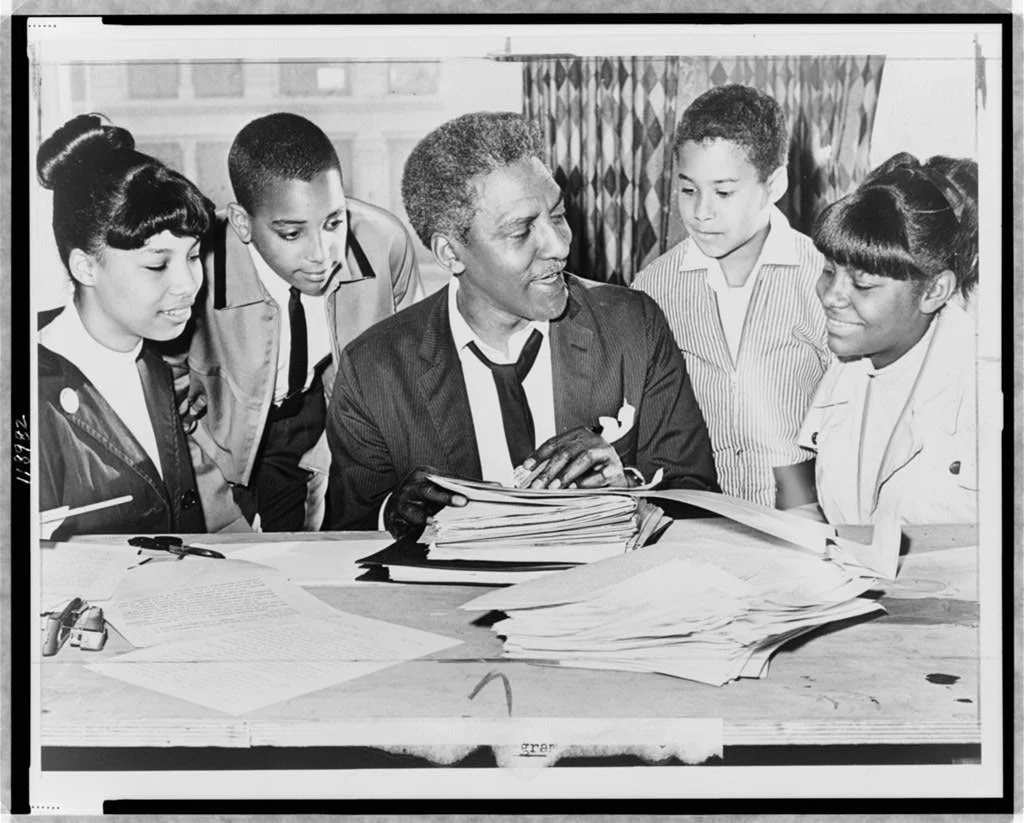

Bayard Rustin (center) speaking with (left to right) Carolyn Carter, Cecil Carter, Kurt Levister, and Kathy Ross, before a demonstration] / World Telegram & Sun photo by Ed Ford, 1964. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c18982

What is Holy Trouble?

The concept of holy trouble—what Rep. John Lewis called good trouble—comes from Gandhian nonviolence. Civil rights leaders embraced this tradition, especially Bayard Rustin, a lifelong Quaker, committed nonviolent activist, and chief organizer of the 1963 March on Washington, who became a key advisor to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Rustin said that every community needs “angelic troublemakers”—people committed to direct, nonviolent action to change unjust laws.

First, a Story

In a letter, Bayard Rustin wrote about an incident that happened to him in 1942 that demonstrates what he meant by direct, nonviolent action to change unjust laws. He writes:

“Recently, I was planning to go from Louisville to Nashville by bus. I bought my ticket, boarded the bus, and instead of going to the back, sat down in the second seat. The driver saw me, got up, and came toward me.

‘Hey, you. You’re supposed to sit in the back seat.’

‘Why?’

‘Because that’s the law. Negros ride in the back.’ *

I said, ‘My friend, I believe that is an unjust law. If I were to sit in the back, I would be condoning injustice.’”

This scene repeated at every stop until the driver called the police. When the police officers confronted him and demanded that he move, Bayard said:

“I believe that I have a right to sit here. If I sit in the back of the bus, I am depriving that child—” I pointed to a little white child of five or six— “of the knowledge that there is an injustice here, which I believe it is his right to know. It is my sincere conviction that the power of love in the world is the greatest power existing. If you have a greater power, my friend, you may move me.”

This was one of many times Rustin was beaten and arrested for resisting injustice.

Note: The driver used a different word—a slur—that I have edited it here. You can read the full account in the book Time on Two Crosses: The Collected Writings of Bayard Rustin.

Nonviolence Is Grounded in Love and Self-Restraint

Bayard Rustin believed that real change requires people willing to peacefully disrupt unjust systems. He didn’t mean chaos or rebellion for its own sake. He meant moral, disciplined, nonviolent resistance grounded in love, conscience, and faith.

It took great self-discipline and training for him to intentionally and nonviolently break an unjust law. He went on to train many others in the Civil Rights Movement in how to break unjust laws in this highly intentional way.

Goal and Intentions of Holy Trouble

Holy and good trouble sometimes means breaking unjust laws and disrupting the status quo. But all of us are susceptible to thinking we’re acting on behalf of a just cause, so it’s important to question our goals, intentions, and accountability. Here are a few questions to help clarify the distinctions:

What motives are underneath our actions?

For whose benefit are we acting? Is what we’re doing good news for the most vulnerable in our society?

Who are we listening to?

What are the fruits of our actions?

What are our asks? Organized movements have very clear and specific demands.

To whom are we accountable?

How do we make sure we are not dehumanizing our opponents, even if they are dehumanizing others? We cannot become like that which we oppose.

Nonviolent, Direct Action

Bayard Rustin was committed to nonviolent, direct action as a path to a more just world. Direct action means taking peaceful action to bring about change, including sit-ins, marches, hunger strikes, boycotts, picketing, street art, and more. Direct nonviolent action disrupts the status quo and eventually makes injustice impossible to ignore.

Direct action must be sustained over time, in community with others who share a common goal. This is not passive at all. In fact, it is much harder and requires much more training and self-discipline to disrupt the status quo without resorting to violence against people who are being oppressive.

Note: Not all roles in a movement are loud or upfront. Many people with every type of talent and personality can contribute in creative and supportive ways.

The Roots of Nonviolence

Bayard Rustin studied nonviolent resistance from Mahatma Gandhi. Gandhi’s decades-long campaign opposing British rule in India succeeded through disciplined, strategic, nonviolent action known as Satyagraha, or “truth-force.” Gandhi’s approach drew on centuries-old traditions of nonviolence found in Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist teachings, as well as the moral example of Jesus and other spiritual leaders.

Rustin was inspired by how these principles, rooted in love, conscience, and moral courage, had been used to challenge and ultimately overthrow an empire. He wanted to immerse himself in the methods of disciplined, purposeful resistance and learn how Satyagraha could be applied to fight injustice in his own country.

As far as we know, Bayard Rustin first used the term “angelic troublemakers” in a speech he gave to fellow organizers in New York City in 1963, just a month after the incredible success of the March on Washington and only ten days after the Ku Klux Klan bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, horrifically killing four young girls. In that speech, Rustin outlined his concept of angelic troublemakers:

“We need, in every community, a group of angelic troublemakers. Our power is in our ability to make things unworkable…The only weapon we have is our bodies. And we need to tuck them in places so wheels don’t turn.”

People Are Never the Enemy

This is one of the hardest lessons of all.

In nonviolent movements, people are not the enemy; instead, the ignorance and systems that lead to harmful acts are the enemy. Dr. King spoke often of the “double victory”: not only are oppressed people liberated, but oppressors come to realize that the systems they are part of are harmful—even harmful to themselves.

This is echoed by Valarie Kaur, a modern-day Sikh leader who leads the Revolutionary Love Project and has been on the receiving end of hate and oppression. She says that the ethic of love does not mean we have to feel warm feelings toward oppressors; rather, it is about refusing to dehumanize anyone. In her book, See No Stranger, Kaur writes:

“No one should be asked to feel empathy or compassion for their oppressors. I have learned that we do not need to feel anything for our opponents at all in order to practice love. Love is labor that returns us to wonder—it is seeing another person's humanity, even if they deny their own. We just have to choose to wonder about them.”

Holding room for the humanity of those committing atrocious acts matters, even if they deny their own humanity—or ours. It is how we stay aligned with the larger goals of holy and good trouble.

Note: You can listen to Bayard Rustin’s speech in 1963 in his own words in this podcast (the intro includes his “angelic troublemaker” quote!).

By Daneen Akers, Author

Holy Troublemakers & Unconventional Saints, Dear Mama God

The audiobook for Holy Troublemakers & Unconventional Saints is now available.

We also offer a full companion curriculum for those interested in diving in deeper.